This blog is focused to explain how vectors work in the backend, and we’ll specially look at push_back method of the vector container. Looking at the source code helps to understand the implementation, and how vectors can be used efficiently.

Vector Containers are type of sequenced containers in C++ commonly uses as a better alternative of arrays. They are also known as dynamic arrays, and as the term suggests - it’s one of the advantages they hold over native arrays in C++. You might have heard of Standard Library containers like vector, set, queue, priority_queue before. They all implement methods defined by the Container Concept.

A few important notes before we start:

- I’m using GCC 10.0.1 which is in the development stage. I’ve built GCC 10.0.1 from source on my local system. But everything I discuss here, should be same with GCC 8.4 or GCC 9.3 releases.

- I assume you are at least using C++11. If for any reason you are using C++98, there might be a few differences (for example, variadic arguments were not present in C++98). To not include lots of macros to check C++ versions, I’ve at times assumed the reader is using C++11 or greater.

- This blog uses lots of C++ Design Patterns that many would not be aware of. I understand it might just be a good idea to explain them first in a blog, but for now - I assume you have at least heard of them and know a thing or two about C++. I’ll cover these in future.

Let’s start with a basic comparison of using arrays and vectors in C++:

// Create an array of fixed size: 10

int* InputArray = new int[10];

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

// Let's assign values to the array

// Values are same as indices

InputArray[i] = i;

}

We can do the same (from what you see above) using vector:

// Include this to be able to use vector container

#include <vector>

std::vector<int> InputVector {};

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

InputVector.push_back(i);

}

While both do the same, but there are many important differences that happen in the backend. Let’s start with performance.

- The piece of code using vector containers in C++ took 23.834 microseconds.

- The piece of code using arrays in C++ took 3.26 microseconds.

If we had to do this for 10k numbers, the performance might be significant:

- The piece of code using vector containers in C++ (for 10k numbers) took 713 microseconds.

- The piece of code using arrays in C++ took 173 microseconds.

As in software development, there is always a tradeoff. Since vectors aim to provide dynamic memory allocation, they lose some performance while trying to push_back elements in the vectors since the memory is not allocated before. This can be constant if memory is allocated before.

Let’s try to infer this from the source code of vector container. The signature of a vector container looks like this:

template<typename _Tp, typename _Alloc = std::allocator<_Tp> >

class vector : protected _Vector_base<_Tp, _Alloc>

Where _Tp is the type of element, and _Alloc is the allocator type (defaults to std::allocator<_Tp>). Let’s start from the constructor of vector (when no parameter is passed):

#if __cplusplus >= 201103L

vector() = default;

#else

vector() { }

#endif

The constructor when called with no params, creates a vector with no elements. As always, there are various ways to initialize a vector object.

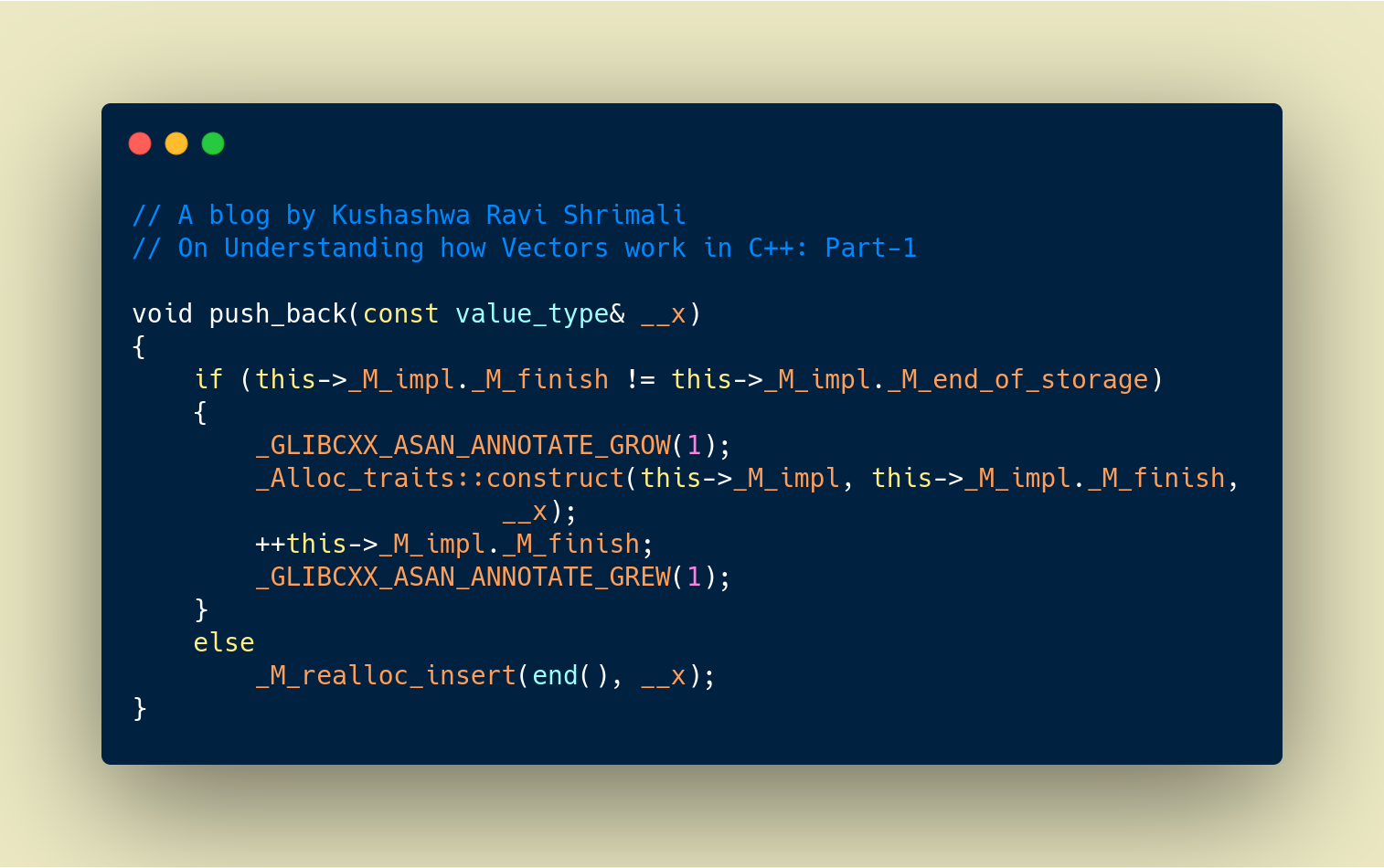

I want to focus more on push_back today, so let’s take a look at it’s signature. It’s located in stl_vector.h file.

// Note that value_type is defined as: typedef _Tp value_type as a public type

void push_back(const value_type& __x)

{

if (this->_M_impl._M_finish != this->_M_impl._M_end_of_storage)

{

_GLIBCXX_ASAN_ANNOTATE_GROW(1);

_Alloc_traits::construct(this->_M_impl, this->_M_impl._M_finish,

__x);

++this->_M_impl._M_finish;

_GLIBCXX_ASAN_ANNOTATE_GREW(1);

}

else

_M_realloc_insert(end(), __x);

}

A few notes to take:

value_type: This is the type of the elements in the vector container. That is, if the vector isstd::vector<std::vector<int> >, then value_type of the given vector will bestd::vector<int>. This comes handy later for type checking and more._GLIBCXX_ASAN_ANNOTATE_GROW(1): The definition of this macro is:#define _GLIBCXX_ASAN_ANNOTATE_GROW(n) \ typename _Base::_Vector_impl::template _Asan<>::_Grow \ __attribute__((__unused__)) __grow_guard(this->_M_impl, (n))- The base struct

_Vector_basedefines these functions and structs. Let’s take a look at struct_Asan. Essentially, all we want to do with the above macro is to grow the vector container memory by n. Since when we insert an element, we only need to grow by 1, so we pass 1 to the macro call.

template<typename = _Tp_alloc_type> struct _Asan { typedef typename __gnu_cxx::__alloc_traits<_Tp_alloc_type>::size_type size_type; struct _Grow { _Grow(_Vector_impl&, size_type) { } void _M_grew(size_type) { } }; // ... };If usage of Macros is new to you, please leave it for now as we’ll discuss more about these design patterns in future.

- The base struct

A note on usage of

_M_impl. It is declared as:_Vector_impl& _M_implin the header file._Vector_implis a struct defined as:struct _Vector_impl : public _Tp_alloc_type, public _Vector_impl_data { _Vector_impl() _GLIBCXX_NOEXCEPT_IF(is_nothrow_default_constructible<_Tp_alloc_type>::value) : _Tp_alloc_type() { } } // more overloads for the constructorThe base struct

_Vector_impl_datagives you helpful pointers to access later on:struct _Vector_impl_data { pointer _M_start; pointer _M_finish; pointer _M_end_of_storage; // overloads of constructors }To go deep into the details is not useful here, but as you would have sensed, this helps us to access pointer to the start, finish and end of storage of the vector.

You would have guessed by now, that push_back call will add the element to the end (observe _Alloc_traits::construct(this->_M_impl, this->_M_impl._M_finish, __x);) and will then increment the variable _M_finish by 1.

Note how push_back first checks if there is memory available. Of course we have limited memory available with us, and it checks if the end location of the current vector container equals the end storage capacity:

if (this->_M_impl._M_finish != this->_M_impl._M_end_of_storage) {

// ...

} else {

_M_realloc_insert(end(), __x);

}

So if we have reached the end of storage, it calls _M_realloc_insert(end(), __x). Now what is this? Let’s take a look at it’s definition:

template <typename _Tp, typename _Alloc>

template<typename... _Args>

void vector<_Tp, _Alloc>::_M_realloc_insert(iterator __position, _Args&&... __args) {

// ...

pointer __old_start = this->_M_impl._M_start;

pointer __old_finish = this->_M_impl._M_finish;

// Here we have passed __position as end()

// So __elems_before will be total number of elements in our original vector

const size_type __elems_before = __position - begin();

// Declare new starting and finishing pointers

pointer __new_start(this->_M_allocate(__len));

pointer __new_finish(__new_start);

__try

{

// Allocate memory and copy original vector to the new memory locations

}

__catch(...)

// Destroy the original memory location

std::_Destroy(__old_start, __old_finish, _M_get_Tp_allocator());

// Change starting, finishing and end of storage pointers to new pointers

this->_M_impl._M_start = __new_start;

this->_M_impl._M_finish = __new_finish;

// here __len is 1

this->_M_impl._M_end_of_storage = __new_start + __len;

}

Even though the above piece of code might scare a few (it did scare me when I looked at it for the first time), but just saying - this is just 10% of the definition of _M_realloc_insert.

If you haven’t noticed so far, there is something very puzzling in the code: template<typename... _Args> – these are variadic arguments introduced in C++11. We’ll talk about them later in the series of blogs.

Intuitively, by calling _M_realloc_insert(end(), __x) all we are trying to do is reallocate memory (end_of_storage + 1), copy the original vector data to the new memory locations, add __x and deallocate (or destroy) the original memory in the heap. This also allows to keep vector to have contiguous memory allocation.

For today, I think we discussed a lot about vectors and their implementation in GCC. We’ll continue to cover rest of the details in the next part of the blog. I’m sure, the next time you plan to use push_back - you’ll know how things are happening in the backend. Till then, have fun and take care! :)

A request

For the past year, I’ve been writing blogs on PyTorch C++ API. I’ve been overwhelmed with your feedback, help and comments. Thank you! This series of blogs on C++, is experimental for now. I love reading source codes, and explaining it to readers. I hope this helps. Please leave your comment and feedback here, or reach out to me at kushashwaravishrimali@gmail.com if you wish. Even if you don’t like this, say it! I promise, I’ll be better next time.