In this blog, we’ll continue diving deep into the source code of Vector Containers in GCC compiler. Today, we will be discussing some of the most commonly used methods of vectors, and how they are implemented.

Before we start, if you haven’t looked at the previous blogs in the C++ series, please take a look here. If you are already familiar with memory allocation in vector containers and vector’s base structs, then you can skip reading the previous blogs and continue here. If not, I suggest you reading them.

Let’s start off with pop_back member function, which essentially deletes the last element from the vector and reduces the size by one. Let’s take a look how it is used:

# Initialize a vector using initializer list

std::vector<int> X {1, 2, 3};

X.pop_back();

for (auto const& element: X) {

std::cout << element << " ";

}

You will see the output as: 1 2. If you are wondering how this works in the case of a 2D vector, let’s take a look:

# Initialize a 2D vector using initializer list

std::vector<std::vector<int>> X { {1, 2, 3}, {4, 5, 6} };

X.pop_back();

for (auto const& element: X) {

for (auto const& _element: element) {

std::cout << _element << " ";

}

std::cout << "\n";

}

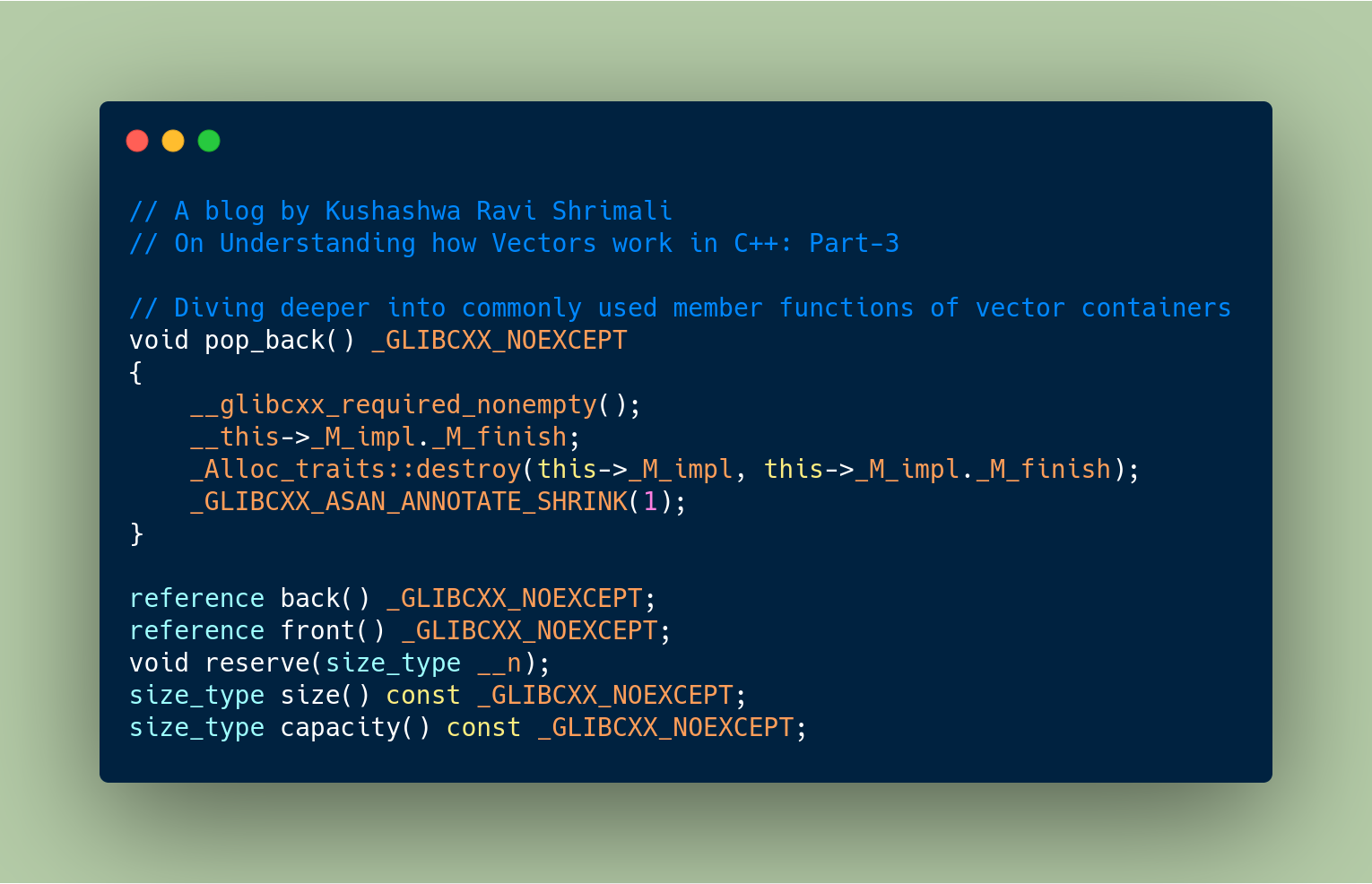

You will see the output as: 1 2 3. As you can notice, it popped back the last element which was indeed a vector. Let’s start diving deep in the source code now, starting with declaration:

void pop_back()

{

__glibcxx_required_nonempty();

__this->_M_impl._M_finish;

_Alloc_traits::destroy(this->_M_impl, this->_M_impl._M_finish);

_GLIBCXX_ASAN_ANNOTATE_SHRINK(1);

}

A short note on _GLIBCXX_NOEXCEPT operator (noexcept since C++11): It returns true if the expression or member function is required to not throw any exceptions. _GLIBCXX_NOEXCEPT is defined as noexcept for C++ versions >= 2011:

if __cplusplus >= 201103L

# define _GLIBCXX_NOEXCEPT noexcept

You can use a condition by using _GLIBCXX_NOEXCEPT_IF(condition) which essentially calls noexcept(condition). One use of this is when you want to access a particular index in a vector, you can avoid check if the location exists or not by using noexcept.

When you call pop_back the design rule first checks if the vector is empty or not. If it’s nonempty, only then it makes sense to pop the last element, right? This is done by using __glibcxx_required_nonempty() call. The definition of this macro is:

# define __glibcxx_requires_nonempty() __glibcxx_check_nonempty()

As you can see, it’s calling __glibcxx_check_nonempty() macro which checks using this->empty() call:

# define __glibcxx_check_nonempty() \

_GLIBCXX_DEBUG_VERIFY(! this->empty(), _M_message(::__gnu_debug::__msg_empty)._M_sequence(*this, "this))

These are typical GCC macros for assertions. If we the vector is nonempty, we now move forward in fetching the last location in the memory of our vector container (using _M_impl._M_finish pointer), please take a look at the previous blogs if you aren’t aware of _M_impl struct. As the term suggests, we attempt to destroy the memory location using _Alloc_traits::destroy(this->_M_impl, this->_M_impl._M_finish). _Alloc_traits allows us to access various properties of the allocator used.

// This function destroys an object of type _Tp

template <typename _Tp>

static void destroy(_Alloc& __a, _Tp& __p)

noexcept(noexcept(_S_destroy(__a, __p, 0))

{ _S_destroy(__a, __p, 0); }

According to the official documentation of destroy static function: It calls __a.destroy(__p) if that expression is well-formed, other wise calls __p->~_Tp(). If we take a look at the existing overloads of _S_destroy:

template <typename _Alloc2, typename _Tp>

static auto _S_destroy(_Alloc2& __a, _Tp* __p, int) noexcept(noexcept(__a.destroy(__p)))

-> decltype(__a.destroy(__p))

{ __a.destroy(__p); }

template <typename _Alloc2, typename _Tp>

static void _S-destroy(_Alloc2& __a, _Tp* __p, ...) noexcept(noexcept(__p->~_Tp()))

{ __p->~_Tp(); }

So clearly, if the expression is well-formed, it will call our allocator’s destroy method and pass the pointer location in that call. Otherwise, it calls the destructor of the pointer itself (__p->~_Tp()). Once successfully done, we reduce the size by 1 using:

# define _GLIBCXX_ASAN_ANNOTATE_SHRINK(n) \

_Base::_Vector_impl::template _Asan<>::_S_shrink(this->_M_impl, n)

As you would see, the macro calls _S_shrink function to sanitize the vector container (i.e. reduce the size by n, here 1):

template <typename _Up>

struct _Asan<allocator<_Up>>

{

static void _S_adjust(_Vector_impl& __impl, pointer __prev, pointer _curr)

{ __sanitizer_annotate_contiguous_container(__impl._M_start, __impl._M_end_of_storage, __prev, __curr); }

static void _S_shrink(_Vector_impl& __impl, size_type __n)

{ _S_adjust(__impl, __impl._M_finish + __n, __impl._M_finish); }

}

We don’t need to go deeper into these calls, but (as per official documentation), the call _S_adjust adjusts ASan annotation for [_M_start, _M_end_of_storage) to mark end of valid region as __curr instead of __prev (note that we already had deleted the last element, so __impl.__M_finish + __n (here __n is 1) will be the old pointer).

A good useful note here is, that pop_back function isn’t marked noexcept as we already have conditions to check the container being non-empty. In case there is any failure, the debug macros are called and throw necessary exceptions.

Let’s go ahead and take a look at a few other member functions (there are many, take a look here: https://en.cppreference.com/w/cpp/container/vector, I only discuss those which are commonly used)

back(): Let’s take a look atbackcall. As the name suggests (and as we saw before), this returns the last element in the vector container. It can be used asX.back()whereXis a valid vector container. Let’s take a look at how it is implemented in GCC:reference back() { _glibcxx_requires_nonempty(); return *(end() - 1); } // definition of end() iterator end() { return iterator(this->_M_impl._M_finish); }Note that

end()points to one past the last element in the vector. That’s why we doend()-1in the definition ofbackfunction. This should now be pretty obvious, that why use assertion_glibcxx_requires_nonempty()as we want to make sure that we are returning valid memory location.front(): It should be very similar to what we saw withback(). This returns reference to the first element of the vector.reference front() { _glibcxx_requires_nonempty(); return *begin(); } // definition of begin() iterator begin() { return iterator(this->_M_impl._M_start); }Note how we use the pointers

_M_startand_M_finishto access first and the last elements of the vector container respectively.reserve(): Some times we want to pre-allocate memory to a vector container. You can do that usingX.reserve(10)to reserve enough size for 10 elements (integers if X isstd::vector<int>type).void reserve(size_type __n) { if (__n > max_size()) _throw_length_error(__N("vector::reserve")); if (capacity() < __n) _M_reallocate(__n); }So when you want to pre-allocate memory, there are 3 possibilities:

- There is already enough memory allocated. No need to allocate. (Case of

capacity() > __n) - There is not enough memory allocated. Need to reallocate memory. (Case of

capacity() < __n) - The required size is greater than maximum size possible, then lenght error is thrown. (Case of

__n > max_size())

- There is already enough memory allocated. No need to allocate. (Case of

size(): This will return the size of the vector container:size_type size() const { return size_type(end() - begin()); }So, let’s say you have reserved memory for 10 elements, then

size()will return 10.capacity(): This returns the size the container can store currently.size_type capacity() const { return size_type(const_iterator(this->_M_impl._M_end_addr(), 0) - begin()); }Here,

_M_end_addr()returns address of (end of storage + 1) location (if the pointer tothis->_M_impl._M_end_of_storageexists).

There maybe a few member functions that I missed, but I’m sure the tutorials so far in the Vectors series are (hopefully) enough to help you out with understanding the source code.

With this blog post, we are also done with the vector series in C++, and coming up next, we will take a look on using all of this knowledge to implement useful utilities for vectors while implementing libraries and projects, and also other design patterns in C++.

Acknowledgement

I have received a lot of love and support for these blogs, and I am grateful to each and everyone of you! I write these blogs to share what I know with others and in a hope to motivate people to not fear when looking at the source code of any library. I think, reading codes is a good practice.

I am thankful to Martin York (aka Loki Astari on stackoverflow) for his constructive feedback on my blogs. Special thanks to Ujval Kapasi for taking time to read through my blogs and giving valuable feedback.

I was, am and will always be grateful to my elder brother Vishwesh Ravi Shrimali (also my all time mentor) who helped me getting started with C++, AI and whatever I have been doing recently. He inspires me.